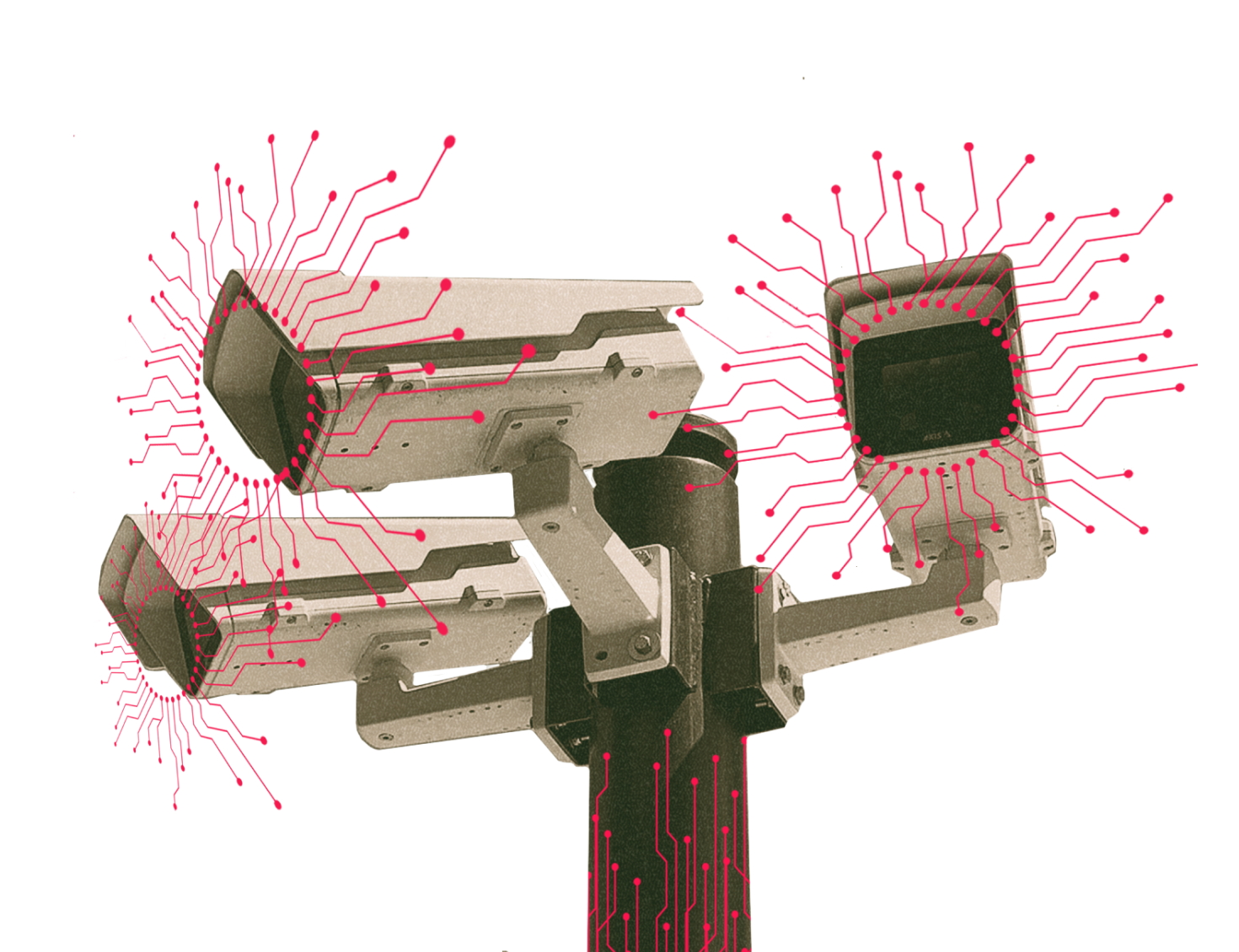

We at the Justice, Equity and Technology Table understand that technology is a form of power that also reflects power within society. As investigators of power around technology, we regard policing as one of the most blatant uses of automated systems to perpetuate structural and institutional harms, continuing histories of oppression and colonisation.

The phenomena of institutional racism and racialised disparities in European policing is well-known. Over the years, there has been an overwhelming body of evidence built by anti-racism organisers and police monitoring groups demonstrating how racialised people are over-policed and targeted. From racial profiling to under-recording of racially motivated hate crimes and repression of grassroots community organisations, racialised criminalisation remains one of the main drivers of social injustice in Europe. It is no surprise then that new police surveillance tech is being directed at the poor and the racialised.

Historical perspectives can help us situate this role of technology within policing. As stated by sociologist Elia Zureik:

“It is significant that the basic tools of surveillance as we know them today (fingerprinting, census taking, map-making and profiling – including the forerunners of present-day biometrics) were refined and implemented in colonial settings, notably by the Dutch in Southeast Asia, the French in Africa, and the British in India and North America.” (Quoted by The European Network of Corporate Observatories)

Consider ankle monitors. Even if someone has not committed a crime, they are nonetheless visibly criminalized, such as in the case of migrants in the UK. Historically, surveillance has been used to criminalize racialised communities; it is no different today. Any attempt to organize against these technologies that ignores their intentionality of it will either fail, or even worse, play into the very logic of their development and deployment.

The Project

Although organisers have formed a solid analysis of the issue of racialised criminalisation, many still grapple with questions about the extent to which and the ways in which algorithmic technologies figure into today’s policing. Our conversations with Table members show a vital need among communities for better oversight, insight and documentation of the harm that is inflicted by new methods of policing. Since the adoption of data-driven policing is still in its early phases, we need to make better sense of the issue in order to sharpen strategies of resistance.

This is What Police Tech Looks Like was born out of this motivation to document and expose experiences of the harm caused by violent and discriminatory technologies. The project asks three main questions:

- How do marginalised communities in Europe experience, grasp and monitor the detrimental effects of data-driven policing and policing in general?

- Which strategies do marginalised communities in Europe follow in the face of discriminatory technologies and racialised criminalisation?

- In which ways can we strengthen our collective capacity as organisers to engage in coordinated cross-border actions?

We embarked on this journey by convening police monitoring and technology monitoring initiatives across Europe in January 2022. The assumption we made was that since these groups have close experiences with the policing activities and technologies being deployed, they are in the best position to lead our understanding of the impacts of police surveillance technologies and building sites of resistance. The convention provided space for a diverse set of organisers to meet, learn from each other, and reflect on common issues. Each organisation presented their work in parallel sessions, so that future collaborations could be forged and tools and resources could be shared. During a follow-up meeting in May 2022, we continued discussing common issues that we have been organising around and the directions that we might take to build power while centring the lived experiences of targeted communities.

Everything starts from getting the trust and being part of an interconnected network with the people on the ground

Monitoring the police across different contexts

Although we are still at the beginning of this journey, we are already unpacking shared patterns across different contexts in Europe. For example, organisers expressed the need to make knowledge about how these technologies work more accessible and digestible to a wider audience. we noticed a complete lack of transparency regarding where data ends up. Another similarity across contexts concerned the actors who profits and who bears the burden; the industry behind these systems vs. poor and racialised communities.

One key point was the role of police monitoring in the broader push-back on policing, as well as how police monitoring can be connected to action. Monitoring violations is an indispensable tool used by activists, researchers, journalists, and communities of resistance to analyse and expose information that states and companies do not want revealed. Indeed, many campaign initiatives against police brutality and injustice have been based on the information provided by police monitoring groups.

However, there are still questions to be answered: Is monitoring and exposing injustice enough for social change? How do we shift the burden of proof from marginalised communities to the state and technology companies? How do we strike a balance between monitoring and translating knowledge into action so that we use our resources wisely. In other words, how do we gain power?

Building relationships of trust

During these exchanges, a shared appetite grew for collective organising. In the coming months, we intend to collectively answer these questions and address potential challenges. As one participant said, “We see the same policing strategies and same technological systems all around the world, which shows the importance of our group here.”

This is What Police Tech Looks Like recognizes that success is a moving target as we will need to adapt our work. Therefore, we want to establish a reflective space which creates the conditions and processes necessary for reliable, inspiring, and supportive relationships to emerge and grow. Instead of assuming that more monitoring and data collection will naturally bring about change, we will root ourselves in the knowledge that we already have and bring it to the exchanges we continue to organise. As another participant put it: “Everything starts from getting the trust and being part of an interconnected network with the people on the ground.” That’s our starting point.■