The STOP LAPD Spying Coalition has been on the forefront in the fight against data-driven policing and surveillance. Their ground-breaking work combines community research to expose surveillance and policing tech, visual and creative tools to demystify new technologies and hands-on organising. All with the explicitly abolitionist aim of building power on the ground to dismantle the carceral technologies of what they have coined the Stalker State. We invited Stop LAPD Spying Coalition members Shakeer Rahman and Hamid Khan to talk about their work and their experiences on research and mapping of surveillance technologies.

From the get-go with our own histories it was clear for us: we are not here to reform the system; we are not here to ask for accountability or transparency or reporting recommendations – we are here to dismantle. And build that ground power.

The community-anchored work of the Coalition contrasts the usual legal or policy avenues by advocates against surveillance technologies. For the Coalition, such methods are part of a problematic dynamic of top-down interventions by experts, who parachute in and reduce the issue to an abstract framing of constitutional violations or privacy invasions. Too much of the knowledge and analysis happens among professionals, lawyers, academics or technologists, which creates distance from the actual impact of these systems on the ground. Dispassionate expert conversations narrowly define how the harms of surveillance are to be understood, as well as the scope of responses. This creates an emphasis on issues of bias or transparency, on debates around constitutional violations, policy and regulation. These kinds of priorities and politics of professionals are not necessarily relevant for the people experiencing the harm most directly, Rahman explains.

The Coalition has always steered clear of these expert-led reform efforts. They are not interested in looking for remedies through litigation and the court system, nor by the political system of legislation and ordinances. “We’ve had enough lawsuits.” says Khan.

The Coalition’s interest are the people who are harshly policed and are, in fact, experiencing the harms of surveillance. They built their base in Skid Row in downtown Los Angeles, a neighbourhood with prevalent poverty rates and unhoused people, as well as a record-high deployment of police per capita. The Los Angeles Community Action Network (LA CAN) is their home – an organisation which is been present at Skid Row for over decades and one of the very few poor people’s movements of fighting back and organising around poverty and homelessness.

“That community is where new surveillance technologies are piloted and tested,” says Shakeer Rahman. “It is where new forms of policing are experimented with. So, it is imperative to ground the work of organising and empowering in that community.”

The insistence that more movement building and grassroots organising is needed, can often count on some level of resonance. “That all sounds cool to a lot of people,” as Rahman observes. “But the question is: how does grassroots organising and mass mobilisation actually look like? How to create that culture of resistance, mobilisation, and responsiveness?”

This is where all their different approaches – from street conversations, community-based research, collective study and popular education – come in. As well, taking sufficient time for every single approach matters too. Initially, Khan and Rahman explain that in their years-long efforts against the stalker state, they have spent a good amount of time just speaking to people on the street: youth in gang databases, undocumented immigrants, day labourers, migrant communities, and unhoused people. These conversations revolved around the experience of being surveilled and of being defined as suspicious. It shaped the Coalition in their thinking and organising, and started a collective process of engagement with the issue.

“I remember having our very first town hall of public unveiling of the research in 2012. Over 250 people in Skid Row came together to speak about surveillance. For me it was the first time that this open conversation on a community level was happening, where we were unpacking some of these things collectively.”

Hamid Khan lists town halls, street theatre, open conversations and educational tools as crucial elements of their work. All of it contributed to a process of taking back the narrative, finding new ways to talk about surveillance together, to demystify technology and expose its systemic character. “A core question has been: how do we bring the story?” says Khan, giving an example of one of the guidelines they developed to speak about surveillance as: ‘not a moment in time, but a continuation in history’. Explicitly surfacing links between for example the 18th-century Lantern Laws and present-day ankle monitors, was to counter the narrative of surveillance as something new, as a post 9/11 or digital era phenomenon.

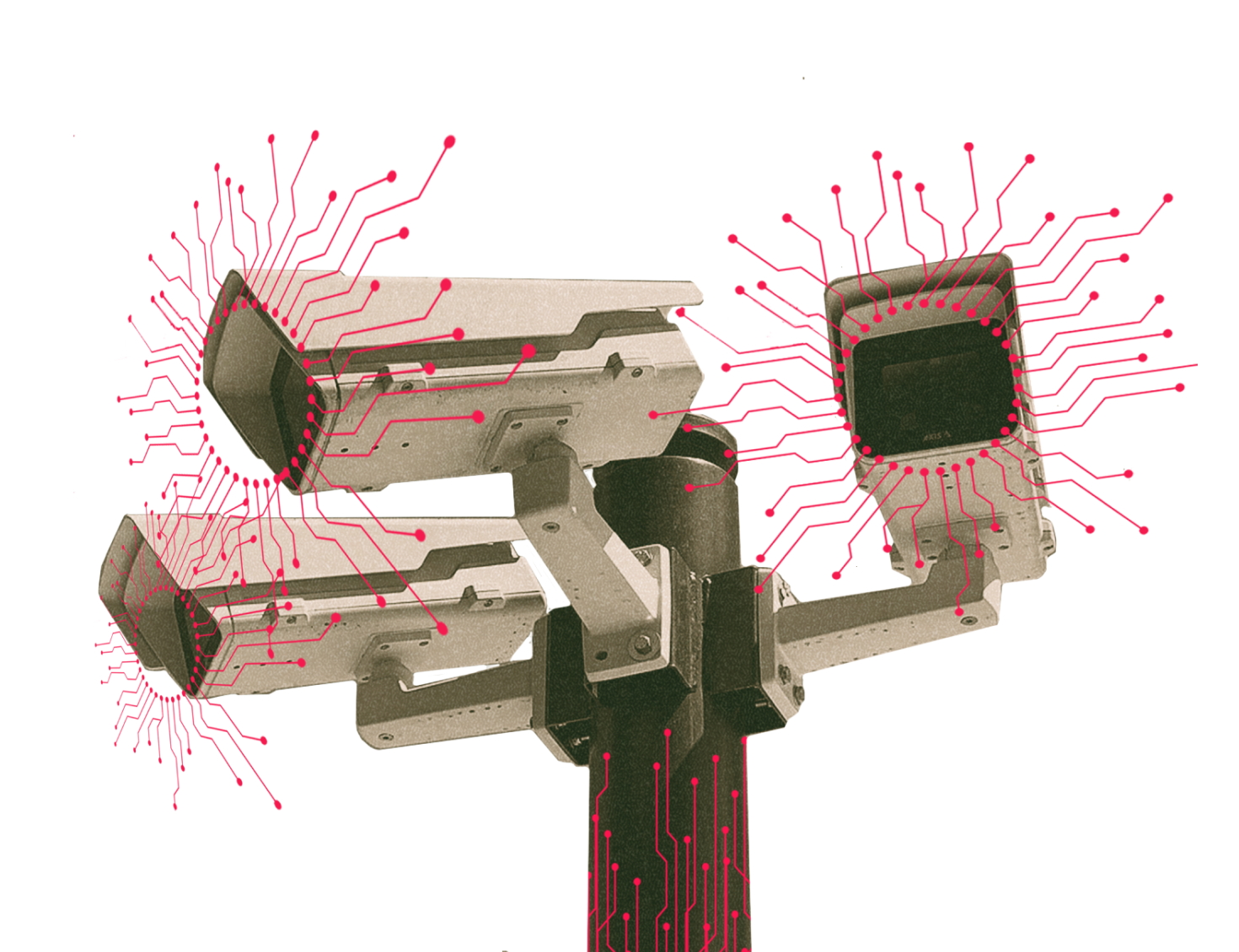

Another method to bring the story, are the many visual representations the Coalition developed to understand and unpack the issue and feed the many conversations as tools for community education. This could as straightforward as providing pictures of surveillance architecture, just to show what something like a licence plate reader looks like. A picture of the actual technology makes it tangible and helps people to recognise these technologies in their streets. Or it could be a more intricate tool, such as The Algorithmic Ecology, which maps out the connections, histories, and political and commercial interests of a predictive policing program (read here how it was developed and how the Algorithmic Ecology functions as both a framework and a tool).

By mapping out these relationships and visually presenting them, the Coalition could show that surveillance goes far beyond individual technologies, or even individual institutions such as the police – but must be understood as developed by a broader ecosystem. Information gathering, storing and sharing happens between a wide range of public sector, private sector and international agencies. The visual tools are essential for bringing this complexity back to an every-day level. “Mapping this out triggers people to have these aha-moments,” Khan explains, adding that looking at it as an ecosystem also contributed to develop a more intersectional understanding of the harms of surveillance, as it moved the focus away from the technologies itself to the broader power dynamics.

“From there the conversations moves to all these relationships. How does the police state intersect with gender and sexuality? How does it intersect with the war on youth? What is data-driven policing and what is the day-to-day political landscape in which surveillance becomes a key weapon and tool for repression and social control?”

It led the Coalition to cast their nets wider. “Not only against the police or particular technologies or programs or policies, but around the whole ecosystem that surrounds that harm.”

The importance of that ecosystem approach and of addressing the role of actors beyond the police, was confirmed by collective community-based research. Moving from spaces of experts towards building power of the communities impacted, community driven research aims to decolonise knowledge production. This meant investing time to make people who were interested, more comfortable with uncovering and analysing public records – work usually done by academics, journalists, or lawyers. The focus of the research was based on questions that community members brought forward. From there, the research would start moving, by doing public requests and surfacing as much information as possible.

Taking time to do the inquiries was essential. “We started to get all these massive records,” says Shakeer Rahman, “Our workgroups started to look at them and for a year of two, before we got to the point of writing about it or trying to make claims, we were really just investigating. It was a process of dozens of community members going through these documents together, trying to figure out what jumps out as interesting, as point for further inquiry.”

When studying the programs and their impact, the Coalition quickly realised these programs never operate in isolation. Of course, the choices of police are influencing the algorithmic inputs and output, reproducing oppressive power dynamics. But these choices are in turn shaped by external parties as well – by real estate developers, non-profits, or academic researchers. A primary example is a hot-spot map created for predictive policing. The Coalition discovered that Skid Row itself was not marked as a hotspot on that map, but the zone around it. They realised that this map was in fact reflective of the dynamics of development, displacement and gentrification that were occurring in this area. The inputs would be coming from those around the edges of Skid Row – the new inhabitants of the area, real-estate developers and property owners.

This discovery opened new areas of investigation. Rahman explains. “Someone was interested to look at how businesses are organised through these business improvement districts that coordinate their surveillance and policing at a private level. Or look at the municipal prosecutor who handles these nuisance related evictions of buildings.” After months and months of work and dedication, the Coalition is now producing a community-based report on the relationship of data-driven policing to displacement and gentrification as well as more deeply to Southern colonialism, to conquest and the ongoing legacy of those institutions, ideologies, and harms.

For Rahman, it is not necessarily the final report, but the process of inquiry which has proved essential. Building research capacity, making the connections during the process, forging a network of collaboration and sharing. “It is really that kind of building of community practise, community knowledge, of expertise. That culture of resistance and culture of collective study. This is what we are building and what we need to develop more in our movements to be able to dismantle.”

Exposing and understanding the broader ecosystem is not just a conclusion of all the conversations and community research, but is a necessary starting point for its dismantling, Rahman says. “You need to look beyond the programs to the broader inputs and ecosystem surrounding them. If you are only fighting against a particular program or system, the response will be: “you are right, that is bad, let’s get rid of that” – after which they come back with a new thing which is in fact designed to be more durable and can manoeuvre around the criticism the community was making. To really address these root causes and dismantle the system, you cannot just be organising against one example. You need to target not only the particular program but the entire ecosystem that surrounds this.”

Rahman’s final observation is that within the ecosystem approach, global connections are crucial as well. Not only because many the surveillance tech companies operate on a global level, but also because policing tactics and strategies are adopted from different geographies. “Policing technologies and methodologies that local police departments use, are directly adopted from the US military’s counterinsurgency operations in Iraq and Afghanistan.” From the use of military equipment by the police to the use of data and technologies, Rahman points out, there is exchange with the military. “There is this direct relation with occupation and imperialism and colonialism around the world. So confronting all of that ecosystem, is another big part of our work.”

Read the new report from on data-driven policing’s relationships to real estate development, displacement, settler colonialism, and conquest, out at http://automatingbanishment.org.

Below are some of the excellent resources as recommended by Shakeer Rahman and Hamid Khan about the work of Stop LAPD Spying. Draw inspiration from their reports, zines or webinars.

Timeline of LAPD Spying and Surveillance [pdf]

Timeline of US Government Surveillance [pdf]

Architecture of Surveillance:

The Stalker State

Policing Strategies and Tactics

Great articles on “police reform” and academic complicity: Surveillance Bureaucracy Expands the Stalker State and as part of ‘A New AI Lexicon’:

Surveillance. The Ghost of White Supremacy in AI Reform.

Among community zines for strategies to push back are zines ( grassroots self defense and principles and Not a Moment in Time)

Reports on the release of the Peoples Audit, on body-worn camera’s, drones and on dismantling predictive policing .

A whole range of webinars to watch here.