“A failure is what society illustrates as my fate

It’s not about the choices we make

It’s what’s given on my plate

While constantly being watched with no options to evolve

I see the chaos all around me so I paused

I had thoughts that making it out must be the best escape

But an invisible chain is instilled in my fate

Man, Carceral Humanism is a fucked-up state

With wealth and plans I must fluctuate

Lead a positive trait to find a way out of this empty space”

- Abdulkadir Ali, Carceral Humanism

ISeeking help in spoken word artist Abdulkadir Ali, his words express unsettling feelings after a session with Monish Bhatia where we discussed the electronic monitoring (EM) on migrants. “Some media outlets are calling it ankle bracelets. It is not jewellery. It is a very serious and sinister technology. Those at the poor end complete the electronic monitoring in very nasty conditions” he puts it frankly.

Monish joined us to share insights into EM technology drawing on his research Racial surveillance and the mental health impacts of electronic monitoring on migrants published in Race & Class.

Technology to reform incarceration?

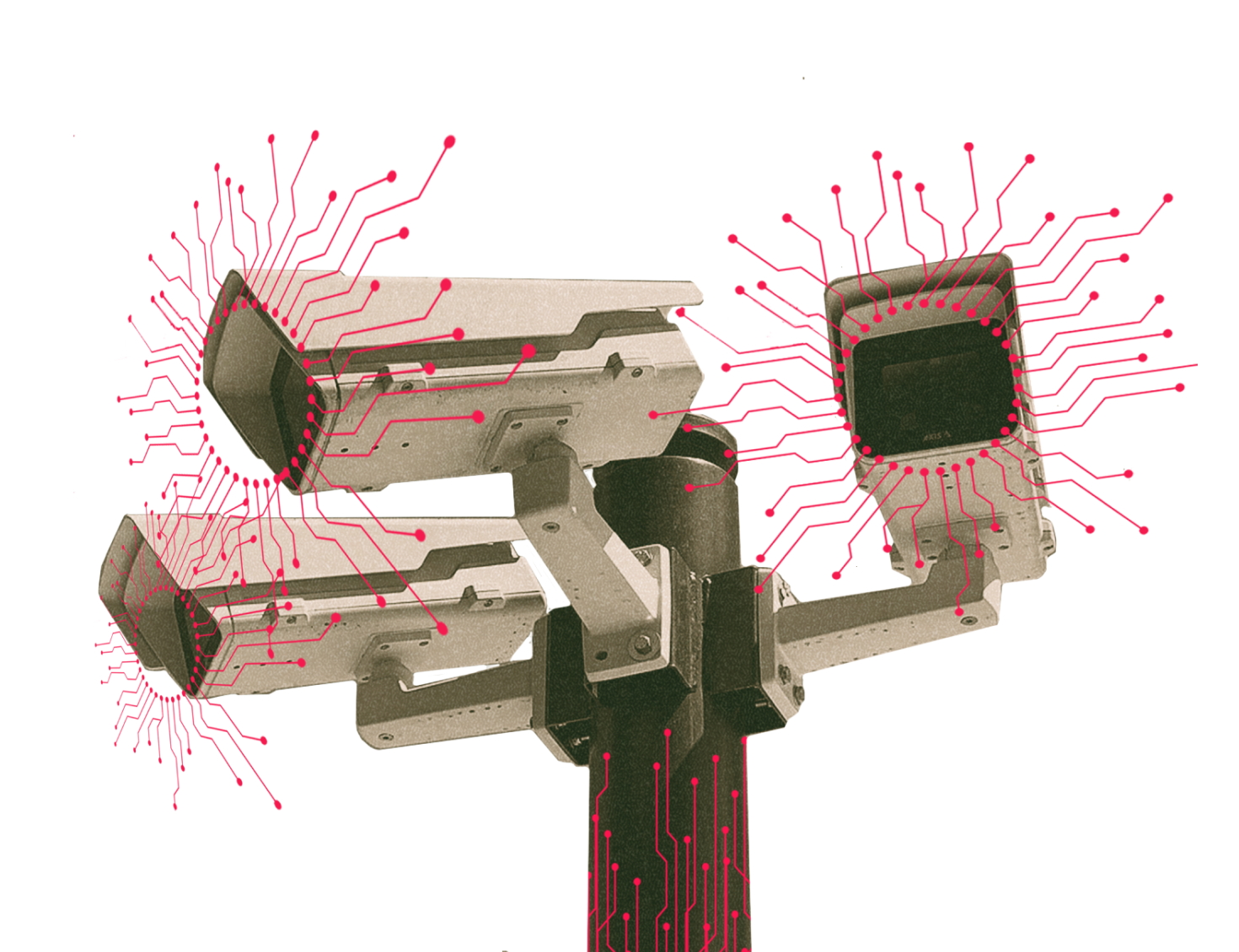

After being first developed and deployed in the US, EM was brought into England and Wales and implemented under the Criminal Justice Act 1991. It was used to track offenders and suspects to check whether they were complying with the conditions for bail or the sentence. The rationale behind the deployment of EM was to reduce prison overcrowding and the costs of incarceration. However, there is no evidence of any reduction in imprisonment. On the contrary, the UK currently has the highest number of people in the world being electronically monitored in proportion to its population.

Reformist approaches to incarceration argue that EM is a softer and more humane form of punishment as it keeps people out of prison. This argument comes in handy for the companies selling the technology such as G4S, that was given a £25 million contract in 2017 by the British government. The cost of running EM between 2017 and 2025 is likely to be around £130 million(not to mention the serious fraud investigations against the company.) We can easily say that EM does not save any money. Additionally, people who are being monitored experience different forms of isolation, loss of liberty and autonomy. They cannot work to sustain themselves and must cope with the dehumanising consequences of being marked as ‘dangerous’ and ‘risky’ in society. In that sense, EM serves as an extension of imprisonment. Reform does more harm than good since more people are being captive due to the net-widening effect of the deployment of carceral technologies. Since this technology of control is available as an option, judges have a tendency to use it for community sanction. “Is the use of EM proportionate? Is it necessary? If there was no EM on the menu, what would a judge do? Would the judge release the person subjected to prosecution?” asks Monish.

Electronic monitoring in immigration enforcement

EM was brought into the sphere of migration governance through the Asylum and Immigration Act in 2004. EM can be used as a bail condition for people who are released from immigration detention. Those who are tagged (subjected to EM) are the ones who were deemed risky for ‘absconding, re-offending and/or seen as having potential to cause harm to the public’ while their immigration cases were being processed. EM is an additional layer of control imposed upon migrants, among others such as reporting duties to the police or immigration offices. An important difference between the criminal justice and immigration systems is that people are always sentenced to EM for a limited amount of time, while this period is indefinite when it comes to migrants. To be clear, immigrants are being subjected to this punitive measure from administrative authorities – even if it is not imposed by the criminal court for an unlimited amount of time (until they most probably get deported). They receive no information as to why and until when they will be monitored.

Defending EM as a form of decarceration plays into the very logic of anti-migrant racism and further criminalisation of migrants, even after they complete their time in detention. Some call this approach ‘carceral humanism’ like in Ali’s poetry ‘an invisible chain is instilled in my fate’. In this case, the chain is even glaringly visible. People are confined to their homes up to 12 hours a day, stigmatised for being child sex offenders (who are also being monitored), obliged to show up at reporting centres that are inconveniently located, exposed to mistreatment of the immigration officers through invasive and arbitrary interrogations and threatened with being put back in detention. For those who are parents also, this has a huge impact on their parenting and family life. Unsurprisingly, systemic dehumanisation of e-carceration takes its toll on their mental health and overall well-being. Rizwan, one of the migrants Monish interviewed, mentioned:

“Sometimes they [monitoring officers] call me to ask: ‘where have you been?’ When I say that I’ve been here or there, then they ask: ‘why did you go there?’ If you don’t go out, they give you a call and ask ‘why have you not been out?’ and once they ask me ‘you are alive, yeah?’ [emphasis added by the participant]. That is stupid! They don’t give me money and they don’t understand that if I go out for anything, even to XYZ [supermarket name] – I will have to spend money…when I was inside in the prison everyone said ‘one day you will be released’. This is not release!”

Resisting surveillance

Even under these difficult circumstances, individuals find ways of resisting these violent technologies and push for the removal of the devices. They raise their voices and create awareness around the harms of EM by approaching elected decision makers in their local area, joining events, delivering speeches, mobilising people around them or seeking justice through legal pathways. One of them, Ali, went on a hunger strike as a last resort in his fight for freedom:

“If I die, I will die with dignity…I will die fighting for freedom. You know in my country people are killed for having an opinion, they are killed because they want freedom. I come here thinking I am free, but look at this thing [pointing towards the tag]. I feel like a prisoner in my own body. I go anywhere, this thing follows me.”

Ali’s hunger strike lasted one week after which he was hospitalised. Eventually, he was free from the electronic shackle. Having been inspired by the resistance of the individuals being monitored, we also reflected on the potential ways of organising around the issue.

Even if the UK is the only country in Europe implementing EM for immigration enforcement, we should be prepared for other countries to follow the same path. Another point of attention is the expansion of surveillance through other monitoring technologies being rolled out alongside EM. Surveillance technologies such as GPS monitors to track people’s movements 24/7, biometric identification to establish where people come from, or phone tapping in detention centres are continuation of colonial practices which made racialised communities “knowable, locatable and contained”. A potential point of intervention is about challenging the assumptions which keeps the system intact. Exposing the harms of EM which extends surveillance to entire communities is direly needed as opposed to the arguments framing it as a humane and softer form of punishment. That should be done by centering the lived experiences of individuals and communities being monitored and amplifying their voices such as the ones mentioned above. EM is incarceration, not an alternative to it.

Monish Bhatia is a Lecturer in Criminology at Birkbeck, University of London. He has published several articles and book chapters, and is the co- editor of numerous books and issues including Media, Crime and Racism (Palgrave, 2018), Critical Engagements with Borders, Racisms and State Violence (Critical Criminology, 2020), Migration, Vulnerability and Violence (International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy, 2020) and Race, Mental Health and State