With our tools of engagement and a strategic approach that centers people, not technology, we index the history of efforts in the tech and justice space, offering building blocks for other network weavers to use, adapt, and improve. In this blogpost, we introduce different spaces that we hold, their origins, and the ways in which they relate to each other.

Building networks has always been core to JET’s approach. There are several reasons for this.

First, the context in which we started our journey was a crisis one, and we knew the urgency of building together in uncertain times. Measures against COVID-19 provided the police with more power and additional tools which resulted in an increase in police brutality and racial profiling. So-called health surveillance coincided with growing far-right nativist, populist, and authoritarian political projects that aimed to shut borders, and target and spread disinformation about ethnic and racial minorities. Meanwhile, states transformed counter-terrorism policies—originally designed to target and criminalize Muslims —into mechanisms that extended policing duties to non-policing institutions such as schools, universities, medical care institutions. By the height of lockdowns across Europe, pushbacks at borders and police brutality reached stunning levels. By and large, technology was a key aspect of the implementation and design of these harmful policies, practices, and narratives, and we recognized immediately that a strong network would mitigate feelings of isolation and helplessness and yield and help us collectively respond to complex problems in uncertain times.

Second, and beyond the COVID crisis context, new forms of policing demand new thinking and action. An increased focus on technology in policing and the invisibility of this technology has amounted to a new paradigm in policing that requires an evolution of practices to address injustice and, therefore, taking time and space to make these changes possible. We carve out spaces where people from different organizational backgrounds can come together without any pressure of delivering an outcome or following a specific path to push for a collective agenda. Many of our network members do use tools such as litigation and policy advocacy to address issues such as racialised criminalisation and state surveillance. However, JET spaces afford an openness and encourage identification of and experimentation with new methodologies, topics, and analyses. We recognize that a learning network can serve as effective base building. Learning together builds trust and relationships, which then in turn build the capacity to act together. As facilitators, JET focuses our convening spaces to be able to provide space for deepening the relationships between organisers. Maintaining this unstructured space and tending to those relationships create fertile ground for emergent strategies.

Third, we also got motivated by a thirst for more substantial changes for racial justice and coordination among social justice organisers across Europe. Many organisers are dealing with immense feelings of despair and anxiety. The challenges we face are massive, yet we need to acknowledge the fact that progressive movements have not marked remarkable achievements in the last decade. By contrast, the far right and conservative forces seem to be able to form a shared vision and strategy across a vast array of actors.

What we need in social justice movements is a long-term strategy and compelling narratives representing a worldview of healthy and safer communities. Attaining that vision requires working through difference, embracing different ways of knowing, and valuing the bigger tapestry of contributions of organisers. Spaces to share lessons learned in ways that uplift each other’s work are a means to cultivate belonging, trust, and joy. They serve as an antidote to those emotions of despair and anxiety. That is the reason why we organise regular spaces of exchange where each participant has something to offer, and, most importantly, people have a great time together. We build agendas in spacious ways where we can discuss what matters the most at that moment for those who are present. Wherever we go, we choose to organise in local spaces (e.g., community centers, squats, art collectives) which leaves us with great memories of finding collective solutions. Our convening participants have bonded when confronting to a leaking ceiling due to pouring rain in Brussels, figuring out where to locate break-out discussions amidst the many tools of a bike repair workshop in Milan, and connecting in a heart-felt way with great hosts in countless other locations. We break bread together in mostly locally catered, community-based restaurants and leave time to chat, unwind, and even dance in local venues. We believe that building relationships cannot be left to coffee breaks.

Different Spaces, Same Purpose

Historically, although JET has evolved and holds many different types of spaces, we approach these spaces with unified purpose. The JET Project is the overarching name for all the moving parts of this initiative, and the JET Table sits at its center. The Table is a core network of thirteen organisations that participate in bimonthly meetings and steer the work of the project. In 2021, the JET staff team (two part-time workers and a mostly volunteer-based principal investigator) and Table members co-designed two principal documents: Table Principles and Collaboration Guidelines. After composing these foundational values and processes, we embarked upon a long-term strategising effort which informed our objectives. We continually revisit and update these on a regular basis. JET now coordinates four spaces in total. We continue to be helmed by the Table. In addition, two new spaces emerged out of the Table: ThisisWhatPoliceTechLooksLike and Refusing Control. A fourth space—Black Data Excavator or BDX—also emerged from the Table as an incubator project. At the core of these three spaces which emerged from the Table are fundamental questions. How can we address the impacts of data-driven policing on racialised communities? What are the potential avenues of support and coordination between different efforts of organising? And how do we envision a world where all people feel safer and live the lives they value?

In short, ThisIsWhatPoliceTechLooksLike brings together police and technology monitoring groups. Refusing Control has worked in local contexts and organised community workshops with on-the-ground organisers. BDX has provided research mentoring to groups in London, Paris, and Barcelona to assist them in connecting issues they face around racialised criminalization with the challenges of new technologies and invisible policing.

Shifting from Exposing Harms to Strengthening Relationships

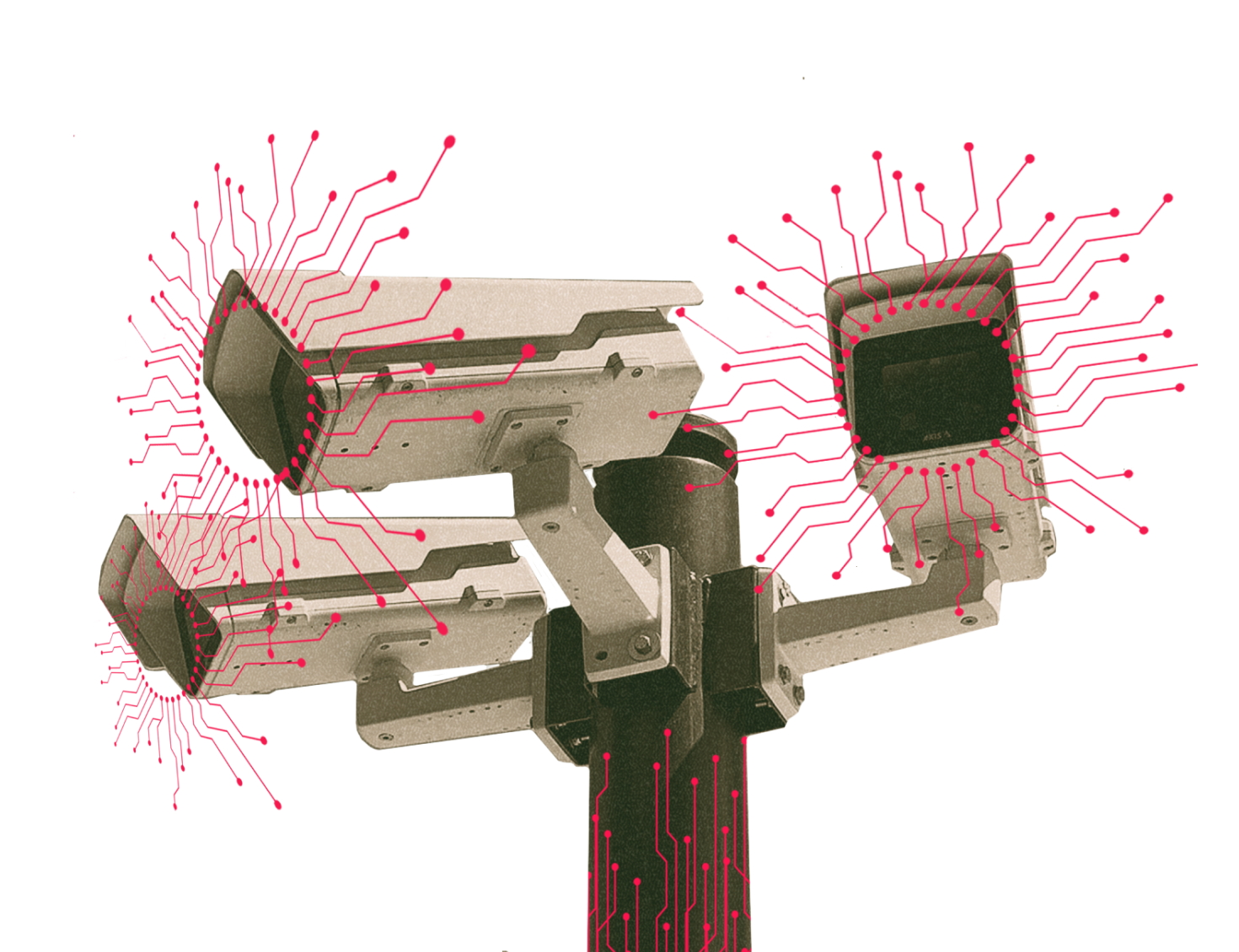

With ThisisWhatPoliceTechLooksLike, questions we had in mind were: How does data-driven policing influence racialised policing on the ground? In which ways do the harms of policing change by data-driven tech? We thought that we could seek answers with a collective of activists and organisers who already document and expose stories and experiences of the harms related to policing and/or surveillance. This space’s initial approach was oriented towards unpacking and understanding harms and documenting these harms with the assumption that it would motivate and inform collective action.

Many police monitoring groups participating in ThisisWhatPoliceTechLooksLike have shared how useful it has been to identify patterns in policing and surveillance across contexts. Similar narratives of risk, threat, criminalisation, and bordering have been weaponized against certain groups, and it has become evident that effective police cooperation is happening. We have also discussed the problems around quantifying harm and engaging in legal processes. Many cop-watchers are turning to people affected in their communities to seek and document the truth, as opposed to engaging in legal processes which are draining and can lead to less impactful or transformative results. With that said, technology—what it is and how it works—often turns into a sticking point, with groups finding it difficult to rely on community experiences.

That is why one of the initial proposals of the ThisIsWhatPoliceTechLooksLike network was building our own police tech database to have better oversight and collect more up to date information. However, after several discussions, we came to the conclusion that we already knew enough and that more data collection would not naturally bring about the change we want. What we needed was to mobilize the trust we held in ourselves and each other to build a collective power analysis. In the end, ThisIsWhatPoliceTechLooksLike felt that what we were doing was already enough: building a channel of communication between police monitoring groups in Europe, something which is a first in our field.

Shifting from a focus on exposing harms to one emphasizing relationships and collective strength has been a major turning point for JET. The relationships that we have built represent what we want, rather than what we do not want. We have embraced a new model of organising and dialogues between the international network of ThisisWhatPoliceTechLooksLike and in-person community workshops called Refusing Control.

Being Transformed by What We Learn

Refusing Control takes the broader picture of racialised criminalisation and new forms of police tech into different local contexts and reiterate conversations with on-the-ground organisers. Refusing Control puts more effort and resources than ThisisWhatPoliceTechLooksLike into organising local events to identify what people need in order to address policing technologies in their context. These meetings have deepened our existing relationships, sharpened our analysis with context specific realities, initiated conversations about technology in racial justice organisations, fortified relationships between monitoring groups within countries and regions, helped groups to formulate political demands, built skills with trainings, and more. Centering in-person community workshops in our work has brought us closer to our intention of rooting ourselves in lived experiences of racialised communities while broadening the movement repertoire of resistance.

After every Refusing Control meeting, we are left with resource lists, lessons learned, action points to be taken, practices of care we experimented with, feelings of gratitude, an experience of being tired and happy, and almost always an unexpected challenge we need to navigate as a group which brings us closer. We then take a pause with those packages we take home. We share back the notes and learnings in other spaces we hold so that different spaces can connect, and conversations can resonate in the whole network. Thinking about how we put our lessons into practice transforms our work while also travelling through communities. Before planning our next step, being transformed by what we learn is what we need most and that ethos of working is what makes JET different from many other networks. Independent from the pressures of funders, institutions, or other systems, JET prioritises trusted relationships as the basis of our collective power.

Space is the Place

JET spaces are places for discovery and building together. Tended to most effectively, they generate new ideas, new relationships, new possibilities. Moving forward, JET will keep on weaving webs of connections which keep us safe, open, and aligned. We are excited to learn more from other network builders about how cultivating connections is powering social change.

Please reach out if you are exploring similar paths of organising, we are always happy to connect.