This blog is to mark the moment in ongoing exchanges between organisers joining the This is What Police Tech Looks Like initiative. In earlier posts (1 and 2), we shared what this space is about and discussed some key points of learning and reflection along the way.

In May 2024, the Justice, Equity and Technology Project convened its first semi-public conference in Athens: Undoing Police Tech, Reclaiming Safety. As an initiative that mostly operated behind the scenes, weaving and supporting interconnected networks of organising, we felt the urge to broaden our circles of inquiry, to engage with a broader set of perspectives against carceral and colonial technologies. The event brought together those who are impacted by the use of police tech – organisers, researchers and journalists – to explore the intersections of social control and data-driven technologies. The second day of the convening was dedicated to the annual gathering of This is What Police Tech Looks Like.

Athens was a pivotal moment of inspiration for that process that is essentially centred around three intentions:

Connections: we hold space to build trust and relationships between people – not only organisations.

Capacity: we facilitate knowledge exchange across contexts and enhance people’s access to resources, training, and analysis.

Container: we create a container where diverse interventions, approaches and analyses can interact to deepen our understanding of the emergent issue of tech-driven social control.

In the last three years, we have met several times to discuss questions of harm related to the use of policing technologies. Each time that we draw parallels between contexts, we see a similar picture of violence: police tech has been proliferated and normalised in many areas of life, and surveillance is always punitive in nature. Despite this dark image in our minds, when we get together in person, we cultivate power over paranoia, resistance over defeat, solidarity over isolation. Finding these pockets of joy and inspiration is integral to the work we do, and it allows us to access a more realistic image of the world rather than the distorted, bleak one

A model of organising and notes for resistance

This gathering was also a moment of consolidation of our collective knowledge and experience on the issue with an eye on finding ways of linking it to action. Taking a closer look at our container, a model of organising started to appear which might be helpful to those thinking about their point of entry to the movement, and to those strategising for what is next.

Most of us organising around data-driven policing contribute to one or more pillars of resistance below. While laying out these pillars, I will weave in some conversations from Athens that stuck with me:

· demystify police tech, expose harms

· analyse, politicise, historicise the issue

· build power: disrupt and repair harms, build visions and practices of justice, safety, collective wellbeing

This framework applies to many social struggles; however, demystifying police tech and exposing harms are especially relevant to the initiatives addressing police tech. Many racial justice organisers and police monitoring groups grapple with questions as to how novel technologies impact racialised criminalisation. As an emergent movement against police tech, we need to unravel the role of technology and make links with the daily experiences of marginalised communities. The opacity and complexity of technologies that are being embedded in social control mechanisms make that unpacking and exposure work even more imperative to resistance.

We need to unravel the role of technology and make links with the daily experiences of marginalised communities

To that end, at the conference, Erase the Database Coalition shared how they managed to unpack the harms of the police crime database called Gangs Matrix in London. Based on daily experiences of the communities they are rooted in, the coalition submitted freedom of information requests about the Gangs Matrix. The response showed that people as young as 13 were on the Gangs Matrix, 85% of people on matrix were Black, Asian, racial minorities. Being on the Matrix increased likelihood of stop and search; some reported 3 times in a day, 100 times in lifetimes, even 1000 times for one person. There are also harms that relate to third party data sharing. Police illegally shared data widely with anyone, unredacted, to random agencies by labelling people as gang members. People’s driver’s licenses were taken away, they were put people at risk of eviction, deportation, removal from schools. Accessing the facts and understanding how the database has been weaponized against racialised communities, the Coalition was able to organise the Erase the Database campaign and shape their course of action. They managed to get the Gangs Matrix scrapped though the use of strategic litigation and forced the police to accept that the use of this database was unlawful.

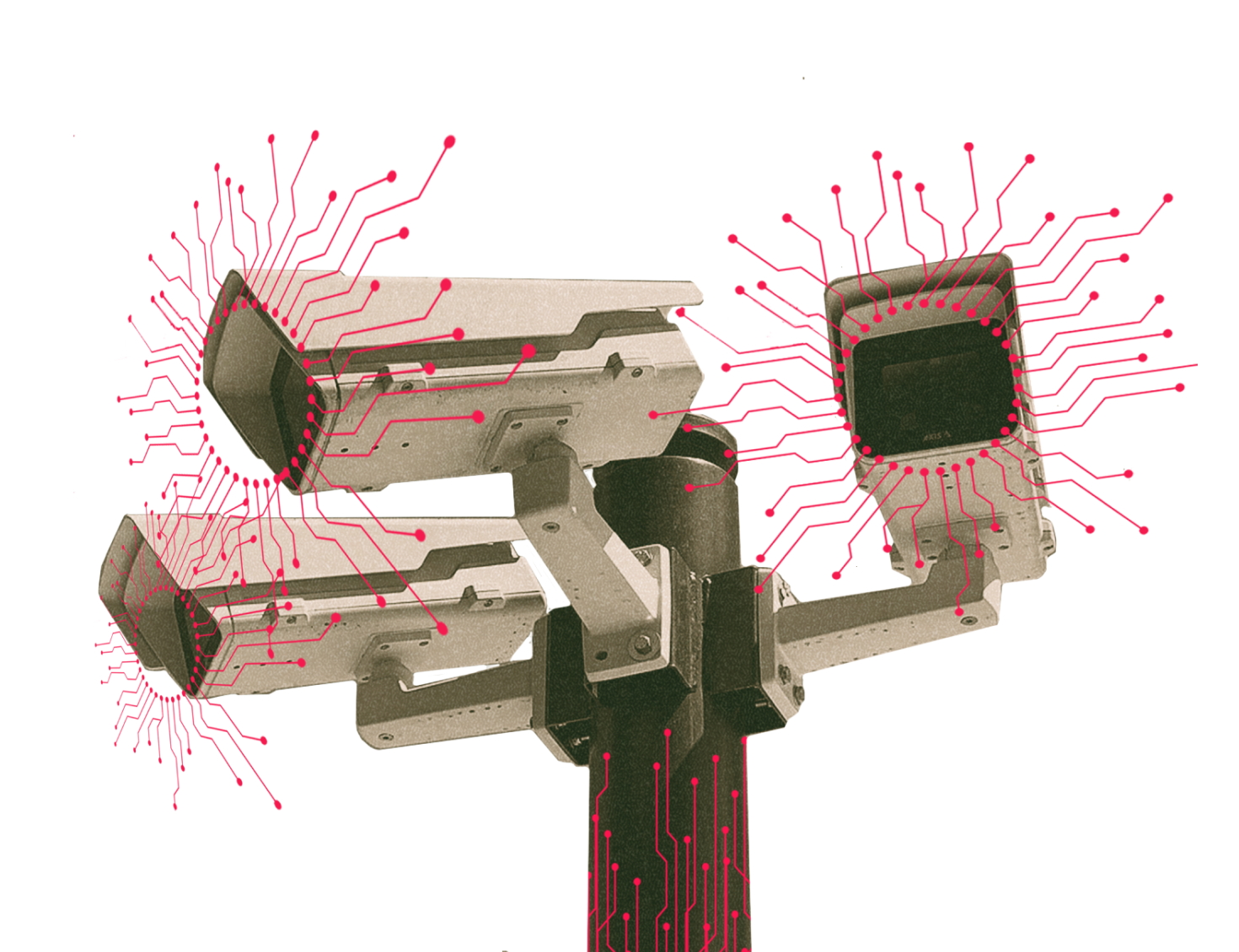

Another strand of organisers focuses more on analysing, politicising and historizing the issue. Without thinking about colonial forerunners of today’s technologies and making links with current power structures in society, we cannot build a consistent theory as a backbone of our resistance. Politicising the issue protects us from intimidating technology-centred discussions and keeps us attentive to what matters most to the people who are most affected. No Tech For Tyrants has done that thought exercise in their report about underlying dynamics by which tech perpetuates police abuse of power. They challenged the myth of protection through efficient surveillance tech and rejected that surveillance brings about safety. Function creep – using surveillance tech more broadly beyond its initial purpose, incentivising data collection, secrecy and obfuscation – are some of those alarming mechanisms they highlighted. For that kind of analysis, we neither need to know how machine learning works, nor do we need to be tech experts. What we need is to be constantly rebuilding our analysis based on facts that are already established: what the police are for, the existence of structural racism, and tech as an aggravating force. A notable example of historizing that we carried out at the conference was the session about the Olympic Games. We put the context and stories of resistance next to each other: Amsterdam 1992 (when the movement eventually stopped the city hosting the games), Athens 2004, and Paris 2024. The Olympics Games this summer in Paris have been instrumentalised to normalise and proliferate police tech such as algorithmic video surveillance, however the instrumentalization and equipping the police during the games is not a new story. CCTV cameras were installed in the context of the Olympics in Athens in 2004 and people knew that this technology was an investment for the police, and it was going to stay. Another constant of the Olympics is displacement of communities – the Roma, migrants, homeless people, students living in precarity. And a note on anticipatory organising – hearing from the successful organising experience in Amsterdam in 1992, a participant from Paris said, “I wish we had this conversation ten years ago.” Another one responded “Since we have that awareness now, is there something we can bring to the next one? How do we use this very long timeline to organize? The police are using this as disruptions.”

Coming a long way and going back

Finally, on the action side, it is about building power in many ways. There are amazing examples of pushing back on the harms. What seems to get postponed in movement spaces are the conversations about how to move from tackling harms to worldbuilding. Challenging dominant narratives and taking abolitionist steps is one way. We discussed the labels of criminality – whether it is a legal category or a state narrative – such as “gang member,” “migrant,” “smuggler” – they are all classified in the same way. These words are being weaponised against certain communities, we need to reframe and disrupt them from the beginning, in the end “these categories don’t actually mean anything.” Building on that, breaking the crime and tech nexus is an important layer here; the whole architecture of surveillance gets accepted and mainstreamed through these fearmongering labels of “terrorism, vandalism” and the like. And it serves the purpose, a lot of money is being made while the power structures stay intact. To reiterate, the political function of technology prevents people from meeting their fundamental needs and derails the conversation away from the failures of capitalism. That bridge between exposing harms to worldbuilding can be built by creating the life-affirming conditions that racialised communities have been ripped off.

The whole architecture of surveillance gets accepted and mainstreamed through fearmongering labels of “terrorism, vandalism”

During these conversations, the usual tension between idealism and pragmatism is palpable. Whenever the idea of a world without punitive institutions or repairing the harms is thrown on the table, it bounces off some people. We cannot ignore that we are pressed by the conditions of today that call for imminent action. In the face of accelerating violence, we might feel the need to push for the solutions even if they do not address the problem at its core. We might engage with the processes of the state, and then as some point, we might get disillusioned about it all. Eventually, how can we heal from something which has not stopped yet? Edward T. Chambers calls it a part of our being: “the tension I’m naming here is not a problem to be solved. It is the human condition.” In that iterative and messy space, what we hold on to is the praxis of movement and community building – both as a process and an outcome. We keep on evolving our responses to complex questions and that in itself changes us and the collective and the society. As Grace Lee Boggs wisely stated: “In this exquisitely connected world, it’s never a question of ‘critical mass.’ It’s always about critical connections.”