When we enter movement spaces and explain we are working on the impacts of data-driven technology, surveillance and police tech, people often respond with hesitation. ‘Oh, I don’t really know anything about tech.’ Or ‘We don’t really work on that.’ Time and time again, we see how the issue of police tech intimidates people. It feels like something irrelevant and alien to their organising or experiences, and way too complex to even start to engage with. This common response is especially worrying, given that many are continuously targeted and highly impacted by surveillance and police tech, often without realising it. Moreover, this response shows us how successfully data-driven technology is framed as an expert issue that requires extensive knowledge before you engage with the topic or even form an opinion about it. It also shows how hard it is to realise the impacts of data-driven surveillance tech on our daily lives, as well as the injustices we try to address. Whether we want to or not, data-driven tech is an issue we must engage with, as it engages with us.

The Veil of Tech

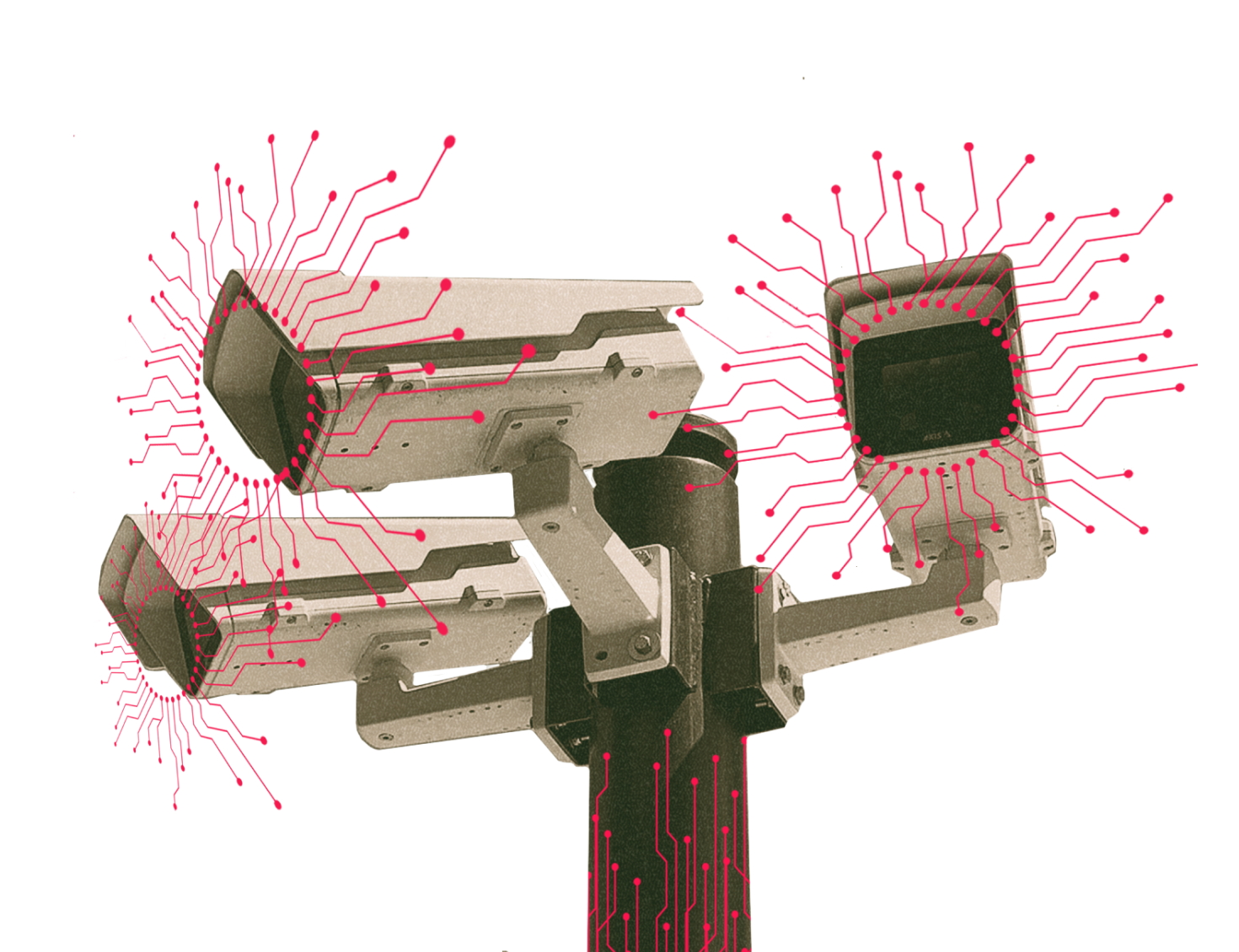

The complexity and jargon that surrounds data-driven tech is one of the ways that police tech hides its workings, according to abolitionist organizers Stop LAPD Spying Coalition. The hyper-focus on technical features of surveillance tools and systems disempowers those who are targeted and impacted by tech-aided discrimination. This expert veil takes away people’s agency to organise and address harm.

This is why demystifying surveillance and police tech with those who are most impacted, is a crucial part of the JET project.

We strongly refute the assumption that you would need to be an expert in data-driven tech to contest the damage it is causing. Think about other, more familiar technologies, like cars. No one would imply that if we would want to address the damage caused by cars, we should first understand exactly how they work. Our argument would be the visible, daily harm of cars, and pushing back against this damage would mean engaging with those who chose to use their power to facilitate cars at the expense of our health, of cyclist, pedestrians, public transport, clean air. Many would understand that addressing the damage done by cars does not require a detailed understanding of car engine mechanics – but it does mean engaging with power structures, interests and underlying narratives.

However, when it comes to data-driven tech, we are often made to believe that we need to be an expert on the issue. Police tech talk tends to obsess over the finer details of how surveillance ‘works’ rather than what power it creates or amplifies.

This is not unique to tech: the jargon-riddled and seemingly abstract sphere of AI and data-driven tech resembles the policy or legal spheres that social justice organisers have had to confront for decades. Intimidating, hard to engage with, and full of gatekeeping mechanisms and attempts to limit issues of power and justice to procedural technicalities.

Addressing the harms of the policy and legal spheres means starting with the daily impact, with our experiences. Time and time again, these experiences tell a very clear story of systemic racism embedded in policy and legal spheres. Thus, the main part of the work of groups pushing back against racist policing, is to monitor and address harms as they play out in everyday, lived experiences. For us, this should be the start of the conversation about the harms of data-driven tech as well.

This is not to say engaging with tech experts can’t be useful. Groups fighting racist policing are often supported in their work by policy or legal experts to engage with these specialised tools of power. The work of a good lawyer is crucial from time to time. Learning about basic rights to guide everyday interactions with the legal system, such as community-focused ‘Know Your Rights’ campaigns or legal support groups, is an important empowering element of the work against repression.

Similarly, engaging with experts of police or surveillance tech can give practical insights as well as support unpacking the institutional ecosystem upholding these technologies. In some cases, deconstructing an algorithm by reverse engineering, shows how it was designed to discriminate against certain categories such as single low-income mums, or includes an over representation of racialised youth. Knowing which company has built the tech, whom they selling to and which arguments are used in their sales pitch, can help identify points of intervention, the underlying narrative and potential allies. In short, collaborations with people with such knowledge can help organizers translate, prioritize, filter out the noise and strategise. But it is definitely not necessary to be an expert of technology yourself, to know how algorithms work or how to code, to have a say about the impact and harm.

Surfacing Everyday Interactions

For this reason, a key part of JET’s work is to developing workshops to unpack the issue of data-driven tech and discrimination in a way that directly links concrete implementations with on-the-ground experiences. Surfacing the many interactions communities already have with data-driven tech—often without realising this—makes people aware it is not some faraway abstract issue. And that in fact, their knowledge and their experiences offer many avenues for intervention.

While there is no shortage of great critical research and reports on discriminatory tech, a clear link to the everyday impact of concrete implementations is harder to find. Therefore, we try to take this research and reports into the field and curate conversations with organisers on what these findings actually mean for on-the-ground realities—how does this play out in practice? JET’s work is anchored in this pragmatic approach. Our workshops build understanding data-driven tech in the context of systemic inequality and racialised criminalisation in relation to what is already unfolding in organising networks.

We will share the workshops and methodologies in the coming weeks and combine them in a playbook to support those who are looking for ways to start the work on addressing the harms of data-driven tech in Europe.

Workshops and Approaches

Examples of the tools we were sharing are our Police Taxonomy exercise, to find concrete examples and surface knowledge about police tech in our environment. This can be combined with the Border Tech on the Move workshop, developed to understand what border tech people on the move encounter during their journey. In the designing of our workshops, we were often inspired by existing practices, and we will include how we used those, for example, the methodology of surveillance walks or the exercise of sketching Movement Timelines. The spaces of exchange these workshops are a part of, were intentionally facilitated to offer the needed space for reflection, which we describe in Holding Spaces.

Together, our methodology and tools have helped us and the communities we worked with, to demystify and unpack the issue of data-driven policing and find avenues to address its impact on racialised and marginalised communities at a local, concrete level.